There is no empty space in art

Martin Holman

In October 1942, Marcel Duchamp provided the layout of an exhibition of Surrealist works to aid inhabitants of Nazi-occupied France. He had been asked to be economical as possible with the installation and string, he knew, was cheap. So Duchamp bought 16 miles of the material and set to work. He wound an almost impenetrable web around exhibits and furniture, connecting framed documents with light fittings, furniture and door handles. The job was done with just over a mile of string used.

Children loved it. They had the temerity to enter the entanglement with confidence. On the opening night, specially encouraged by Duchamp to make it their playground, they adapted the erratically fastened skeins for skipping, football, hide-and-seek and other distractions. I have not found any juvenile testimony of the quality of the exhibition but the descriptions of that first night by adults attest to their pleasure at its presentation.

Everyone else (I imagine that to mean ‘adults’) had difficulties with finding their way to the paintings. The environment was so off-putting that they began to complain about the children. “Mr Duchamp told us we could play here,” was their retort and no doubt set off as much head-scratching as irritation among the puzzled guests.

We cannot know for certain Duchamp’s intention for his design. Refreshingly, and in exemplary fashion, he never felt the need to explain himself. But it is unlikely that he had chosen to upstage his peers; even if scene-stealing was in his character, a charity event was hardly the occasion.

No, maybe the Frenchman’s sublime Dadaist act was provocative for a constructive reason. One thought is that it reminded visitors that play occupies an essential part in our attempts to make sense of the world we inhabit and, as art is closer to the hub of that world than our higher-educated selves will often admit, to make sense of the art we see. We put aside the educative properties of play far too soon in our lives.

Or, just as persuasively, Duchamp wanted to make physical a metaphor for the difficulties, endlessly articulated in newspapers, then and now, that the layman is presumed to encounter (and often does) in attempting to interpret modern art.

Interpret or, as some still describe it, to “understand” modern art. Duchamp would have recoiled from attempts to “understand” his work. And it’s my belief that art does not exist to be understood. And, by and large, comprehension remains elusive, perhaps even by the artist who made it. The question mark hangs over much of what we look at.

Moreover, that is especially true of work classified as “modern art” or “contemporary art”, two more distinctions that I do not accept as existing. For our experience of art is always contemporary, regardless of its chronological era. Even though one cannot underestimate the part history plays in revealing its references, the best work transcends epoch.

Instead, art thrives in the present moment and from its earliest forms has remained, at its progressive edge, beyond the non-practitioner’s ability to “get it” from the idealism of Hellenistic sculpture to Braque and Picasso’s Cubism or, indeed, Duchamp’s re-evaluation of the object "to put art back in the service of the mind." I looked today at a painting that Titian completed in the 1510s; my approach to it hardly differed from the appraisal a serious piece of new work deserves by a living artist.

Thus, I maintain that art thrives in the present moment. From its earliest forms has been the outcome of questions asked by its makers and by its observers, the people on the receiving end, as it were.

The types of questions can be categorised, and academics and theorists have done so. They are formal, aesthetic, emotional in nature, among other bases, and they come out of memory, fantasy, reason and the irrational. Already, just the mental image of this invisible computing and comparing seems to be filling the space between the observer and the observed like numerous light beams cutting through the atmosphere.

For the artist, questions emerge from certainty or doubt, struggle and ecstasy, need or indulgence, the repetitive and the unique. These are among the emotions and states of mind that thicken the atmosphere in the studio, a place that is prison and playground to the artist, as well a manifestation of that person’s artistic past, present and aspired for future.

Questions often support or, even, generate the struggle that is an integral part of making, the need to make another painting, object or whatever. Questions, therefore, can help to justify another picture. They are proofs of creativity within boundaries, and they may arise from a patron’s instructions, the circumstances of the most competitive art of former eras or, more perniciously and the reality of much made now at the most progressive level, from the stranglehold of expectations, the artist’s own or those of others.

Anyhow, back to Duchamp’s room. I mention it because the idea interests me of making physical patterns of behaviour, thought, attitudes and the mental processes of absorption and reaction. The reason for this is a conviction that experiencing art is as three-dimensional as walking through high wind, playing a contact sport or, even, illness. The experience is fully sensual and its parameters go beyond the visual assessment of formal attributes of colour, line and surface and the mental decoding of them into a narrative with which the viewer can occupy the pictorial space imaginatively.

While I am writing, there are several weeks to go before this exhibition opens in Manchester. But the form it has in my imagination is already more than a linear arrangement of different-sized rectangles on a whitewashed gallery wall. Perhaps I have allowed visual documentation of Duchamp’s astonishing installation influence my mind. But what happened in that private ballroom at 451 Madison Avenue in wartime New York City could easily serve to illustrate what happens when an artwork falls under the gaze of a thinking spectator. Or maybe it’s more accurate to offer this image of mental ping-pong as representing what an artist hopes will happen. The air will move.

The photographic record of the Duchamp room resembles one of those photographs in which a person’s movement within a space has been traced in beams of light. Or when lines are drawn across an image to follow the trajectory of the human eye back-and-forth between points of interest. We could settle for it being a combination of both, at least, if not more phenomenological events. No longer a mere container, the space in which the meeting occurs and its architecture become curiously energised. A foreign terrain opens up to the senses. They wrap around and across and up and down the place in the effort to deduce the significance of the object of their attention.

I suppose what I mean is that I conceive of the project (and, indeed, of any successful exhibition) three-dimensionally. That may be illogical bearing in mind the concentration of Head to Head on painting. Where dimensions are concerned, painting can only really claim two. But the show is not only about painting. Its particular appeal is to stress the encounter with paintings as well as the paintings themselves, and we can apply that experience to other art forms, like sculpture, installation, photography, film.

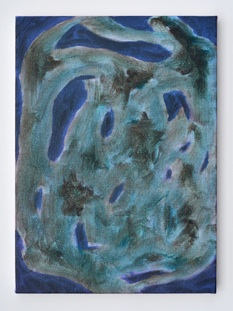

The choice of the organisers (two painters) to restrict their thesis-inducing project to painting has the unexpected effect of heightening awareness of our physical and mental behaviour. Why? Because, in spite of its millennia-long existence, painting is arguably less seen in early-twenty-first century exhibitions than its volumetric or time-based cultural compatriots. For all its ancestry, painting has become to seem, perhaps momentarily in its grand historic span, strangely novel.

Whether paintings are images in their own right or figurations of a reality familiar from the everyday, they have, by their nature, the epidemiology of propositions; once released, hypotheses have the tendency to multiply and spread. Some, inevitably, are easily contained and eradicated. But others settle with a viral insistence, incubating rapidly before presenting the recipient beneficially with keys to a kind of thinking.

Pairing makers, placed together deliberately and with discretion by the selectors, anticipates dialogue. It extends the existence of their work from the flat plain that typically hosts painting into open debate by virtue of the equally open mind that, coming upon them in a location dedicated to that purpose, seeks to interpret that surface into significance.

At that point, the turnover of many ideas activates mental space. If we can correlate that mental space with the place a body occupies, you might then begin to share my view that this exhibition emphasises on something – or some things – more than registering visual representations.

Taking account of painting in this physical way inevitably underlines the fact that observation brings art out of latency and into its active mode. What sight does is to complete the circuit, just as the “on” switch releases charged current. The chain reaction that ensues somehow ionizes the air of the gallery within the intimate exchange between observer and object. Another viewer will have an independent and equally intimate intellectual encounter within a shared, public setting.

Inspiration is often depicted as a bolt of lightning. Well, meteorological dramas on that scale are less common in the atmosphere around art. But they happen, depending on the mix of negatives and positives the visitor brings to the task. At different altitudes possible new perspectives on the familiar can flash overhead. Or a point of view opens up, as literally as Duchamp’s string parodied the entanglements of art, that we were never before so lucidly aware of experiencing.

None of this is easy. No guarantee exists that the connection will spark. That is not because of any failure of intelligence by either party if, on the one hand, the painting is charged to start with and, on the other, the observer is willing to receive. Compliance does not come into it, in much the same way as no gallery space deserves to be passive.

The space that art occupies is electric, although sometimes the current does not flow.

© Martin Holman

21 January 2013